“I didn’t purposely set out to start a company. It evolved from the circumstances I found myself in and the path I was on. I’ve worked in Agritech for a long time but it wasn’t called Agritech when I started.” Bridgit Hawkins, the Chief Sustainability Officer for CropX Technologies.

Hawkins grew up on a sheep and beef farm outside Taupō before qualifying from Massey University with an agricultural science degree. While working in business development and science commercialisation roles in the primary sector, she was frustrated at the disconnect between Research and Development (R&D) teams in universities and research institutes, and the practical realities of what the farmer was dealing with on the ground.

“There are so many people in universities and in R&D roles beavering away without pausing to think, ‘How will this solve a problem for the farmer?’” she says.

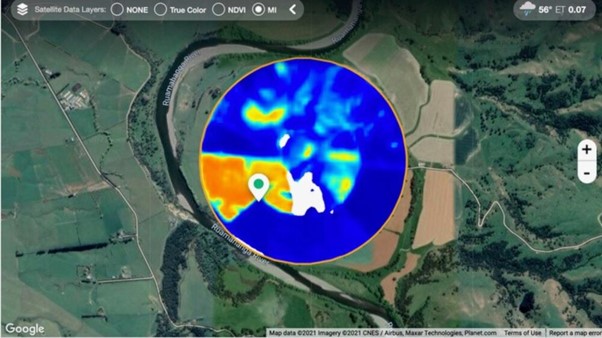

Hawkins partnered with Massey University to develop decision support systems based on sensor technology that provides farmers with real, practical insights. The technology analyses weather, soil, and other environmental data to provide science-backed recommendations for effluent and irrigation management. It results in less runoff of fertilisers and effluent meaning less pollution in our waterways. It also helps farmers track their council regulatory requirements and saves them money. Hawkins founded Regen in 2010 to commercialise the technology and help farmers make better decisions.

“It wasn’t a success from the start because startups are really hard work,” says Hawkins. “Convincing people to change is hard work. People are very resistant to change, not just farmers. But think about the challenges food production systems face around climate change, environmental sustainability and animal welfare. What’s needed is individual farmers doing things differently every day.”

Regen supports farmers to improve their practice by providing them with accurate, timely information. Hawkins knew the concept and the technology that made it possible had value not just in New Zealand but in other markets around the world. She also knew that the company she built didn’t have the capacity or capital to grow a global customer base.

“We realised that we could ruin ourselves and the company by trying to go global,” says Hawkins. “We had shareholders who were willing to put more money into the business but the question we asked ourselves was, ‘How far can we take this on our own?’”

Hawkins took a different approach. She decided to look for a strategic partner for Regen.

“We got to a point where it was difficult to grow organically at the rate we needed,” she says. “One of the hardest things in Agritech is your channel to market. How do you actually get customers? We knew we had a great product and good customers in New Zealand but we figured working with a global strategic partner was the most effective way to build our customer base overseas.”

Regen put out some feelers in the marketplace and as is often the case in a small country like New Zealand, it’s not what you know but who you know. One of the Regen directors was also an investor in Israel-based CropX and he connected the two companies.

Ten years after Hawkins founded the company, CropX, a global leader in digital solutions for farm operations, acquired Regen in September 2020 and incorporated the technology into their in-soil data and farm management analytics and automation tools. Overnight, Regen went from being a company with a solid customer base in New Zealand to working with a global player.

Ironically, CropX had evolved out of initial work carried out by Manaaki Whenua (Landcare Research), a New Zealand Crown Research Institute, before moving to Israel. Finistere Ventures, a major player in the New Zealand Agritech community and an early investor in CropX, supported Regen with the acquisition negotiations.

COVID-19 lockdowns and travel restrictions meant a deal was negotiated without meeting in person. That was challenging for a number of reasons, not least the cultural differences between New Zealand and Israel.

“The CropX team from Israel are incredibly direct people,” says Hawkins. “When we first started talking with each other, if I disagreed with something I’d let them know in a very New Zealand way. They had no idea I wasn’t happy because I was too polite. Likewise, they’d disagree with something I’d say and I’d think, ‘God, that’s rude.’ But I learned we have different ways of communicating. If I knew back then what I know now I’d probably have held out for a better deal, but at no point have I regretted the decision.”

Partners in the primary sector

“… don’t underestimate the value of becoming part of a larger team… It’s not just about growing the business; you can also grow as an individual.” Bridgit Hawkins, CropX

CropX acquired Regen but it’s been much more of a partnership than an acquisition according to Hawkins.

CropX acquired Regen but it’s been much more of a partnership than an acquisition according to Hawkins.

“They couldn’t have replicated the code or the data or the knowledge base we’ve built over ten years and we couldn’t have gone global in the space of 12 months like we have done,” she says. “It’s not just about the capital; it’s about their knowledge, networks and approach to things. It would’ve been a lot more painful and a lot higher risk if we’d tried to do it ourselves.”

Another motivating factor for Hawkins was the impact that her company and technology could have on farmers around the world.

“That’s why I started the business in the first place,” she says. “I passionately believe in the value of the primary sector and how important it is to New Zealand as a country and for the people who work in the sector. We need to be lighter on the land in everything we do but at the same time, farmers feed us every single day. They need to be able to stand up and feel proud about being a farmer.”

The results have been better than I imagined,” says Hawkins. “I thought CropX would come in and take over and I would exit after a period of time. But it hasn’t worked out that way. Personally, it’s been great to work with a team of intellectual, like-minded people who understand agronomy and farming. Running a company from New Zealand can be very lonely but now I’m part of a global science team.”

“Don’t underestimate the value of becoming part of a larger team. Building a small company, you have hardly any peers and that’s a really hard place to be. When you get into something bigger you find there’s all these other people like you. It’s not just about growing the business; you also grow as an individual.”

Reality bites

Lots of New Zealand Agritech companies grow to a certain point and then plateau. That doesn’t necessarily mean they don’t have good ideas, but they may not have enough capital, or the know-how to break into global markets,

“I look at some Israeli companies and there’s generally a level of maturity in terms of the commercial skills of the people in business that’s hard to compete with,” says Hawkins. “Here in New Zealand, we might throw a few million dollars at a few kids who come up with a good idea in university but are they going to learn enough, quickly enough to compete on the world stage? From a technology point of view, Kiwis are just as smart, but sometimes we lack the business smarts.”

Hawkins says the government agencies like New Zealand Trade and Enterprise (NZTE) and Callaghan Innovation do a good job of supporting Agritech companies but building a strong network of your own is crucial.

“Along the way you meet people further ahead in the journey than you and you can learn a lot from other people,” she says. “It’s important to know when you’re pitching and when you’re seeking support because they are two very different conversations.

“We’re a small country so we should be encouraging collaboration, not competition. How can we work together so everyone benefits? Some companies are so determined to win in their space they view anyone doing something similar as competition instead of someone they could collaborate with. We should look for common ground as opposed to the things that make us different. Identify the challenges we all share and work together to solve those.”

In terms of how companies can position their business to make it attractive to potential investors or strategic partners, Hawkins has some simple advice.

“You need to sell the vision of what you think the business can be. You need to tread a fine line between the current reality and the future potential of the business. Think about what you can bring to the partnership. It’s got to be more than just your technology or your Intellectual Property (IP), particularly if the investor can get that somewhere else.”

“When it comes to negotiating with investors or buyers you need to listen to the market, not just the voice in your head that tells you that your business might be worth more than it really is. I’m not saying to undersell yourself but it’s not very common that an international company will swoop in, offer you twice as much as you thought you were worth, and it’s all kittens and puppies. More likely they’ll offer you a third of what you thought you were worth. Somewhere in between is usually fair. You need to balance your ambition and aspirations with reality.”